For disorders driven by a known genetic component, research understandably focuses on developing a drug targeting that genetic signature. When that works, the outcome benefits patients but the end result is still one drug for one disease. The scientists at Alltrna are pursuing an alternative: a single drug that treats many diseases. The startup aims to accomplish this goal by engineering a particular type of RNA to address a feature underpinning hundreds, potentially thousands of diseases.

Cambridge, Massachusetts-based Alltrna now has a $109 million cash infusion to support the work to bring its research closer to human testing. The Series B financing announced Wednesday was led by Flagship Pioneering, the startup creator that founded Alltrna.

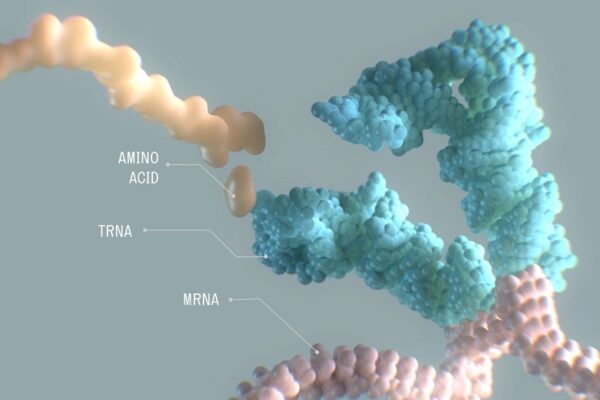

Problem proteins are the root cause of many diseases. In some of these disorders, the trouble is traced to a protein of improper length. The protein-making machinery of a cell links together amino acids, forming a chain in a process that ends with a genetic instruction called a stop codon. In some cases, a premature stop codon halts protein synthesis. The truncated version of the protein causes a disease.

Alltrna’s research focuses on transfer RNA, or tRNA. These molecules are responsible for transporting amino acids to the cell’s protein-making machinery. Alltrna engineers tRNAs to recognize premature stop codon mutations, also called nonsense mutations. These therapies deliver the correct amino acid to restore production of full-length protein. Alltrna refers to these disorders broadly as “stop codon disease,” a term that encompasses many diseases driven by truncated proteins stemming from premature stop codons. Michelle Werner, CEO of Alltrna, says this unifying causative feature offers the potential for a unifying single treatment.

“What’s super exciting about the work that we’re doing is the tRNA has an opportunity to be a universal tool,” said Werner, who is also CEO-Partner at Flagship. “It’s the only universal component of the protein translating process. It does the same job no matter the protein.”

Alltrna’s financing follows its first reports of proof-of-concept data. In May, the company presented data at two scientific gatherings: the annual meeting of the American Society of Cell and Gene therapy and the TIDES USA conference. The company’s presentations showed that its platform can design, modify, produce, and deliver engineered tRNA oligonucleotides.

The Alltrna tRNAs not only read premature termination codon mutations, they also restored protein production. In vitro testing using human-derived cells and in vivo testing in an animal model of a rare disease led to the restoration of expression of full-length protein. In the mouse tests, Werner said Alltrna demonstrated that an engineered tRNA can rescue protein, leading to a ten-fold increase in protein levels. It’s hoped that these therapies will be long lasting, but the biotech is keeping its options open for redosability. Unlike some genetic medicines delivered with adeno-associated viruses that can only be dosed one time, Alltrna’s research includes lipid nanoparticle formulations that permit redosing.

Diseases caused by premature stop codons include Duchenne muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, and cystic fibrosis. Werner, whose experience also includes senior oncology positions at AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Bristol Myers Squibb, said some cancers are caused by premature stop codons. Alltrna isn’t disclosing the disorders it is researching, but Werner said the company’s initial focus is rare disease.

With the potential for an engineered tRNA to address many conditions, the first human test of an Alltrna tRNA might be in multiple rare diseases, Werner said. The strategy borrows from the research of cancer drugs that target particular genetic mutations. A so-called basket trial enrolls patients whose cancers all harbor the same mutation, regardless of the cancer type. This approach essentially tests one drug against many cancers. In rare disease, a basket study offers the potential to reach diseases that may have been overlooked. Many rare diseases can be included in the basket, as long as they have a stop codon mutation that can be addressed by Alltrna’s engineered tRNA therapy.

The basket trial strategy also fits with where health authorities think rare disease research should go, according to Werner. She said regulatory officials in the U.S. and Europe have told her that research needs to get out of going disease by disease and instead embrace a “many diseases at a time strategy” in order to address the many thousands of diseases in need of new treatments.

Alltrna isn’t the only company researching tRNA-based therapies. Last year, hC Bioscience launched backed $24 million in Series A financing for its engineered tRNAs. The Cambridge-based startup hasn’t disclosed details about its pipeline. Tevard Biosciences, yet another Cambridge-based biotech, is developing suppressor tRNAs and enhancer tRNAs. The company’s lead disease indication is Dravet syndrome, a rare form of epilepsy with few treatments. Similar to Alltrna, Tevard says that because many diseases share the same premature stop codon, the same suppressor tRNA can potentially treat multiple diseases.

Werner said Alltrna stands apart from others in tRNA research with its platform technology, which enables it to optimize tRNA nucleotide sequences and modifications for these programmable medicines. She added that the machine-learning component of the technology makes predictions that enable Alltrna scientists to select which tRNAs to move forward. There’s also potential to take the tRNA tech platform beyond premature stop codons, exploring its application in other types of mutations.

Alltrna launched in 2021, backed by $50 million from Flagship. The firm was the only disclosed investor in the Series B round, which Werner said will support the preclinical research needed to advance its tRNA drug candidates to the clinic.

Image by Alltrna